In an ever-changing world of book-bannings and regressive social laws in the United States, it is imperative to acknowledge and celebrate the unique trajectory and invaluable contributions of black artists throughout history. As a black artist myself, I’ve had countless uphill climbs in this industry, whether it be fighting to get my first book published or navigating who to trust on a business level.

The experience of my people’s art has changed me again and again and again. A gift from the past for the present that will undoubtedly change our future. So I wanted to take some time on Millennial Writer Life in a series of posts to explore this.

Roots of African Art: Celebrating Heritage and Spirituality

African art finds its roots in the rich and diverse cultural heritage of the continent. From the intricately crafted sculptures of ancient Nok and Ife civilizations to the vibrant textiles originating from West Africa, and the profound symbolism of masks and carvings across numerous tribes, African art serves as a visual chronicle of a collective identity deeply entwined with cultural traditions and spiritual beliefs. It embraces a holistic approach, blending aesthetics with functionality, and reflecting a profound reverence for nature and the spiritual realm.

Recently, I watched the amazing documentary, Finding Fela, and found myself so moved by this slice of African history that moved me so deeply.

As a continent with so many layered histories, I want to devote a good amount of my art practice to diving into the diaspora and drawing my own conclusion. This is why I’ve recently enrolled in a Pan-Africanism Summer School with The People’s Forum here in New York City.

As the celebrated Nigerian author Chinua Achebe once stated, "Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter." African art serves as a testament to the resilience and creativity of a people whose narratives were often overshadowed or silenced by colonialism.

The Harlem Renaissance: Pioneering a Black Cultural Renaissance

I started learning about the Harlem Renaissance recently when I was hired to write a response piece to a legacy exhibition for the gay, British artist and filmmaker, Isaac Julien. Julien is a vital part of the New Queer Cinema, which sprouted out of the 1980s.

Through his distinct artistic style and innovative storytelling techniques, Julien has helped shape and advance the new queer cinema movement, offering a platform for marginalized voices and promoting greater representation and inclusivity within the film industry. His groundbreaking films, such as "Looking for Langston" and "Young Soul Rebels," have garnered critical acclaim and have been instrumental in elevating queer cinema to new heights, inspiring a generation of filmmakers and artists to explore and celebrate diverse queer narratives on screen.

While watching “Looking for Langston”, I also did a deep dive into the Harlem Renaissance. The Harlem Renaissance of the early 20th century stands as a pivotal moment in the history of black art and culture. It was a time of immense creativity and cultural explosion that reverberated far beyond the boundaries of Harlem, New York City. The Renaissance challenged the prevailing stereotypes and limitations imposed upon black artists, providing a platform for their voices to be heard and their art to be celebrated.

Some artists, like Aaron Douglas and Archibald Motley Jr., sought to depict the vibrancy of black life and celebrate the beauty and resilience of the African American community. Their artwork embraced the concept of art for art's sake, focusing on aesthetic qualities and the power of visual representation. They believed in the transformative potential of art to challenge societal norms and redefine black identity.

In contrast, other artists, such as Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, viewed their artistic practice as a means of social and political commentary. Their works delved into the harsh realities of racial discrimination and sought to shed light on the experiences of black individuals. They believed that art had a responsibility to address social injustices and act as a catalyst for change.

Within the Harlem Renaissance, there were also those who embraced a more introspective and spiritual approach to art making. Figures like Augusta Savage and James Van Der Zee explored the depth of personal expression and the power of individual narratives. Their works often depicted the inner emotional lives of black individuals and celebrated the rich tapestry of human experience.

This spectrum of differing beliefs about art-making among black artists during the Harlem Renaissance showcased the diversity and richness of perspectives within the movement. It reflected the complexity of black identity and the multifaceted nature of the artistic journey. Each artist brought their unique vision and voice to the table, contributing to the collective tapestry of the movement.

The Black Arts Movement: Art as a Vehicle for Social Change

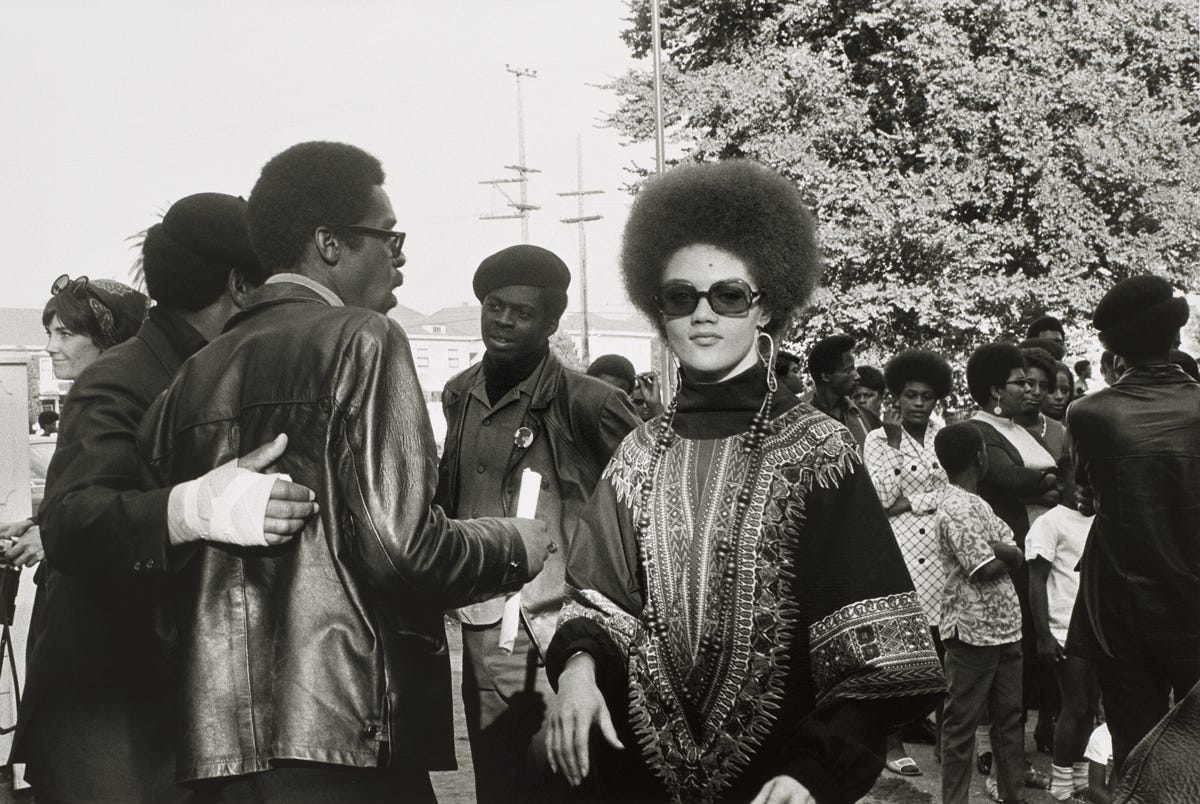

The Black Arts Movement emerged during the Civil Rights and Black Power era in the 1960s and 1970s as a significant cultural and artistic movement within the African American community. It developed largely in reaction to the systemic racism and state violence faced by Black people in the United States.

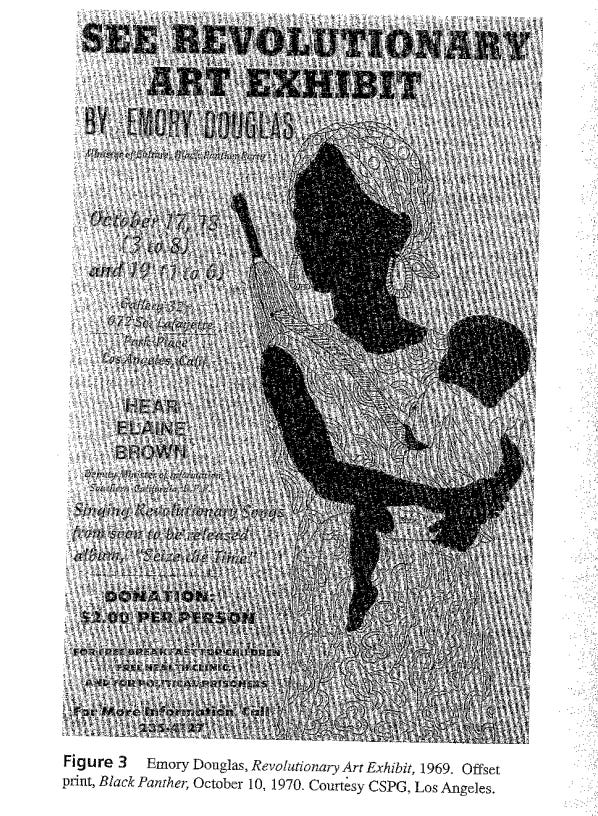

A major central force in this movement was The Black Panther Party. Founded in 1966 by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, it began as a program to approach the revolutionary process through the lens of self defence, community education, and eventually survival programs, like their breakfast program for neighborhood children. Art, in many ways, was at the center of how the Black Panther Party hoped to move people.

In Revolutionary Art Is A Tool For Liberation, Erika Doss writes:

Contesting mainstream caricatures of black men, the Panthers also defied middle class and liberal representations of black masculinity tentatively put in place by the leaders and followers of the civil rights movement. The Panthers projected black power, not egalitarianism. If Martin Luther King Jr. tried to challenge dominant racist stereotypes by claiming black men as citizen-subjects, the Panthers subverted that civil rights image by reconfiguring and romanticizing black men as the very embodiment of revolutionary rage, defiance, and misogyny. "We shall have our manhood," Eldridge Cleaver insisted in Soul on Ice (1968), adding, "We shall have it or the earth will be leveled by our attempts to gain it."

Angered by the limited field of integration and autonomy that the civil rights movement had achieved, alienated by older, "establishment" patterns of political activism, and incensed by their ongoing status as second-class Americans, the Bläck Panthers (like other black liberation movements of the 1960s) "sought to clear the ground for the cultural reconstruction of the black subject.

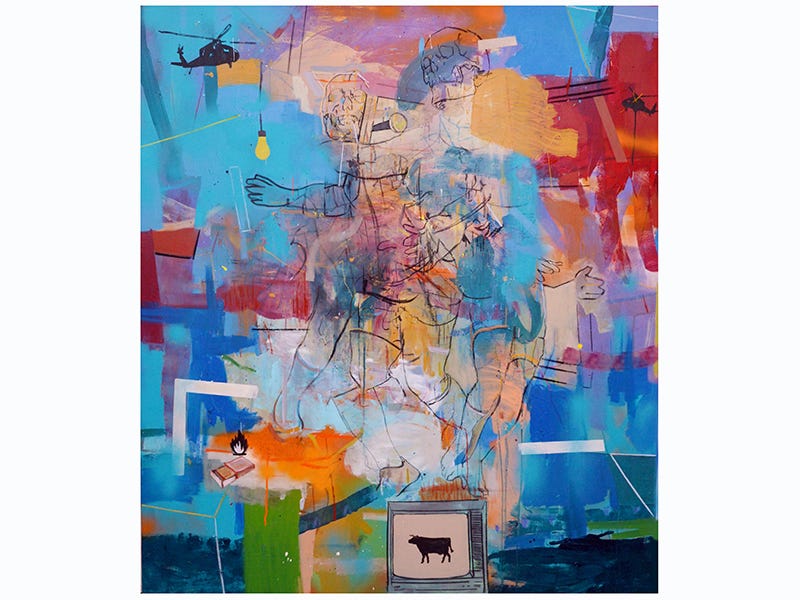

The Black Arts Movement was deeply rooted in the social and political realities of the time. It sought to challenge and dismantle the oppressive structures that perpetuated racial discrimination, inequality, and violence. The movement's artists, writers, poets, musicians, and performers aimed to bring about a profound cultural revolution that would redefine the Black experience and challenge mainstream narratives.

One of the main objectives of the Black Arts Movement was to establish a distinctive and authentic Black aesthetic. Artists sought to create works that reflected the lived experiences of Black people, their struggles, triumphs, and aspirations. They wanted to reclaim their cultural heritage and express it in ways that were free from white artistic conventions and standards.

Poetry played a significant role, with poets such as Amiri Baraka, Sonia Sanchez, and Nikki Giovanni using their words to confront societal injustices and express the collective Black consciousness. Their poems spoke directly to the experiences of Black people, addressing themes of racial identity, pride, and liberation.

Artists like Romare Bearden, Elizabeth Catlett, and Jacob Lawrence used their artworks to challenge racial stereotypes, depict the struggles and achievements of Black individuals, and celebrate Black culture. They sought to redefine the artistic canon by introducing new perspectives and aesthetics that were grounded in African traditions and Black experiences.

Playwrights such as Lorraine Hansberry and August Wilson created works that centered on the Black experience, exploring themes of identity, family dynamics, and social injustice. Hansberry’s play, “Raisin In The Sun” made its debut on Broadway in 1959. It was the first play written by an African American woman to be produced on Broadway, and it resonated deeply with audiences of all backgrounds.

By providing a platform for Black artists to showcase their talents and express their unique perspectives, the Black Arts Movement aimed to empower and uplift the Black community. It sought to challenge the dehumanization of Black people perpetuated by racist systems and stereotypes, presenting an alternative narrative that celebrated the richness and complexity of Black culture.

Books on the Harlem Renaissance:

"When Harlem Was in Vogue" by David Levering Lewis

"Harlem: The Making of a Ghetto" by Gilbert Osofsky

Books on the Black Arts Movement:

"Black Fire: An Anthology of Afro-American Writing" edited by Amiri Baraka and Larry Neal

"The Black Arts Movement: Black Aesthetics, Modernism, and the U.S. Racial Crisis" by Emory Douglas